Is It Possible That We Are Winning?

Novak Djokovic’s Australian Open victory has the distinct feeling of an omen

What can I say about Novak Djokovic’s historic Australian Open win that has not already been said?

Beyond the obvious sporting prowess it bestows, having matched Raphael Nadal’s all-time record of 22 Grand Slam titles, and resecuring his spot as world number one, there is of course the even more sublime victory – his triumph over the petty, pencil-necked Australian Government who grandstanded on the issue of Novak’s refusal to take the Covid ‘vaccine’ ahead of last year’s Open, and subsequently had him deported.

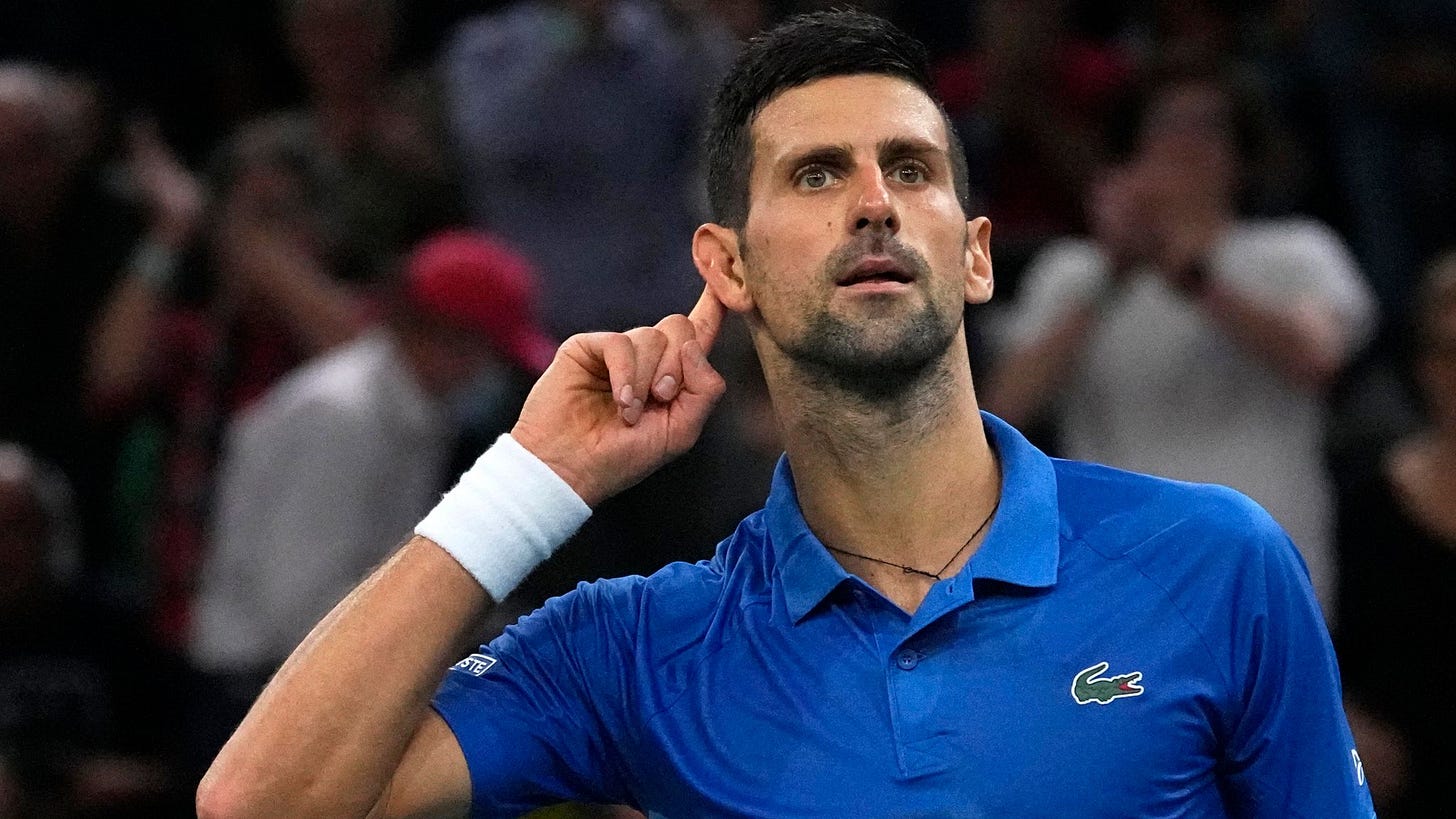

But Twitter and the rest of the internet is awash with gloaters already, the general sentiment most wonderfully encapsulated in this single image:

I’m not sure I can add much, and I’d be saying nothing original or profound by pointing out the delicious irony of Novak’s win in the context of his stance on the vaccine, and the abysmal way he was treated not just by our state and federal governments, but by regular Australians.

It bears repeating however, if only to satisfy my own personal urge to gloat – that Novak came back a year later, obliterated everyone in his path (with a hamstring injury no less), and won the final in straight sets before hoisting aloft the Norman Brooks Challenge Cup, is the single greatest sporting F-YOU in history.

But there is a deeper significance also, one which perhaps transcends the empirical realm and seeps into the ethereal.

It’s difficult to find the haters amid the outpouring of admiration for tennis’s GOAT, partly because the overwhelming support Novak has from the masses is drowning out any snide counter-narrative, but also because the vaccine nazis, government shills, and authoritarian types who took a lascivious kind of pleasure in Novak’s humiliation last year appear to be somewhat more reticent in 2023. Funny that.

Still, the evidence of their malevolence is out there, and they really don’t like it when you call them on it.

Move on, they say – like The Atlantic back in October when they published this tone-deaf drivel in which author, Brown University Professor Emily Oster, called for a “pandemic amnesty”.

Move on? I’ll repeat what I said in my initial critique of the Atlantic article: Uh, yeah – that’s a NO from me dawg.

Authoritarian psychos like Karen Sweeney and their apologists like Emily Oster are naturally eager for the rest of us to ‘move on’ now that their particular brand of fascism is no longer in vogue, and the revelations of the Pfizer documents and mounting global excess death data illuminate the grave miscalculation made by so many credulous fools in the early days of the ‘pandemic’.

These folk backed the wrong horse and, like the worst offenders in any fog of war scenario, now that the lights have been turned back on, they are frantically scuttling this way and that, like beetles and silverfish beneath a suddenly lifted paver, looking for crannies and dank recesses into which they can wriggle and wait out the tide of righteous resentment.

But the forced flippancy these people display as they casually suggest an amnesty for their vile behaviour, and nervously retort “Move on. I have”, is indicative of something that I hadn’t until very recently begun to consider – something that is all the more powerfully symbolised in Novak’s victory.

Could it be that we are winning?

Last week I tacitly criticised elements of our movement for being overly optimistic about the resignation of New Zealand’s self-styled socialist tsarina, Jacinda Ardern. And while I still believe that a long and painful struggle lies ahead, and that a return to common sense, decency and humanity may yet elude us, the marquee events of the past year or so would indeed suggest that the tide may be slowly beginning to turn.

Elon buying Twitter; the rise of the US Republican Freedom Caucus; Ardern’s downfall; the bombshell Pfizer exposé by Project Veritas; Novak’s victory… These events and many others do have the feeling of omens, if one believes in such things.

Even the recent imprisonment of Andrew and Tristan Tate speaks not of an ascendant regime, audacious in its actions for lack of credible opposition, but of a nervous and erratic tyrant, much like Adolf Hitler post-1941, after failing to knock Russia out in one swift summer campaign.

When one reads accounts of the war in 1942, the general consensus was that Hitler still had the upper hand, and indeed he did, as the map shows.

Many, if not most people, on both sides, still believed at this point in history what had appeared self-evident for two years or more – that Germany would win the war.

But we now know that 1942 was the beginning of the reversal of Hitler’s fortunes. These defeats were manifest and measurable at the time, but stacked against his momentous gains, they failed to make much of an impression – the failure to take Moscow, the protracted and costly North African campaign, these were minor setbacks. But they were also the first of many ever-escalating crises for the Wehrmacht – the first major one coming early in 1943 at Stalingrad after which Hitler the nervous, erratic tyrant became Hitler the scared, chaotic madman.

No one could predict this unravelling in 1942 – victory still felt a long way off, and in many respects it was. But this is the thing – history as it unfolds does not readily reveal its hand, and time is relative. As such, the adage ‘with the benefit of hindsight’ is as integral to the human experience as love, loss, and laughter, both at the personal and universal level.

On balance, things still seem bleak. But could we be about to witness a Stalingrad level victory for our side? And will the globalist regime devolve from the nervous erratic tyrant into the scared, chaotic madman?

Herein lies a very real danger, that as the establishment loses control, it is likely to thrash about in a blind rage, throwing out increasingly desperate gambles in the hopes of snatching victory from the jaws of defeat and, like Hitler, taking many down with it.

It is entirely possible this process has already started and that in fact the Covid con itself was the first of these brash gambles. As such, my ostensibly divergent positions of last week and today, may in fact both apply simultaneously.

The tide may have turned. 2022 could have been our 1942. There has certainly been cause for hope, especially on the heels of a somewhat lacklustre WEF annual meeting in Davos, and the vibe in our camp has been cautiously optimistic of late, both in alternative media and more mainstream outlets like Sky News Australia and the Spectator Australia.

But the war will roll on. For how many years we cannot tell. We’re in the eye of the hurricane and there’s no shortcut out. The road ahead remains hard and uncertain, and while breathtaking events like the resignation of Ardern, and Novak’s victory may hail or simply symbolise our final ascendancy, stacked against the gains of our enemies to date, they fail to have any material impact.

But symbols are important. Hope is important. To quote everyone’s favourite rebel, Andy Dufresne: “Hope is a good thing, maybe the best of things, and no good thing ever dies.”

We need heroes like Andy Dufresne and Novak Djokovic who are willing to crawl through the river of shit to come out clean on the other side – they remind us that we all have that fighting spirit inside us, if we’re prepared to dig deep enough.

I believe in symbols, in heroes, and in hope. They shine resplendent before us in times of strife, and sometimes they make us smile and chuckle also, like when the man who became a pariah for the freedom movement in the darkest days of our tyranny came swaggering back into Rod Laver Arena and not only beat the Aussie favourite who apparently jeered at him when he got deported, but won the Grand Slam too – with a frigging injured hamstring to boot!

Whatever your thoughts on God, you’d have to admit that if he does exist then he’s not without a wry sense of humour. In fact, I think if God was on Twitter, he’d be a masterful meme lord – please forgive the pun.

They say he moves in mysterious ways and that’s for certain. But I think he also moves in very obvious ways too – grand story arcs of struggle, redemption, and justice.

We saw one such story unfold at Melbourne Park this week, and it was a real corker.