What makes a great story? Essentially it must have an arc – the protagonist must undergo a journey of change, usually manifested through struggle and adversity. But it also needs a simple, compelling theme. The human art of storytelling is as old as our very species and its power lies in its ability to distil the complex human experience down to canonical, relatable truths.

The theme of any great story will resonate with every human because it is common to all human experience – love, resilience, coming of age, letting go… There are many themes that underpin the great stories of our species, but perhaps none more essential than tragedy and hope.

It was during the unravelling of the 2020 US Presidential Election that I was struck by the timeless theme of tragedy, as it became clear that the brief flame of hope which Donald Trump’s populist ascendance represented was shortly to be snuffed out by the neoliberal establishment’s ‘fortification’ of the vote.

My contemplation of this classic theme of tragedy brought me to the adjacent motif of the rise and fall – and here I made my first connection to The Great Gatsby. With the forty-fifth president’s unprecedented indictment by a Manhattan grand jury last week, the meteoric rise and fall of Donald J. Trump has never been more relevant, and so let us examine the remarkable analogy of Jay Gatsby.

Many of us read The Great Gatsby in high school or college. Some will have picked it up further into their adulthood, perhaps after seeing Baz Luhrmann’s vivid 2013 homage starring Leonardo DiCaprio. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s book is an American classic – perhaps the American classic – and its four film adaptions are testament to the novel’s enduring power. But why does this story still capture our imaginations a century later?

Because The Great Gatsby is not only a tragedy, but also a story about hope.

Hope gives our lives meaning. It gets us out of bed when we’d rather sleep all day; it propels us across the room to speak to a dazzling stranger even while our throats constrict in terror; it is even said to be able to cure cancer. Hope is not only what keeps us going when things are bad, but also what makes us strive for a better world.

In Jay Gatsby’s case, his strife was inwardly focused, and the better world he desired had him at its centre with Daisy Buchannan beside him, forever.

Trump detractors will agree that the Donald’s presidential ambitions were equally self-serving, and the strength of my thesis here does largely rest on whether one reads Gatsby (and Trump) as a sympathetic or objectionable character. Personally, I find much to like and dislike in Jay Gatsby, and the same goes for Donald Trump – I do not worship the man, but I still believe he’s our best short-term shot at halting the tide of woke globalism and derailing Agenda 2030.

A lifelong fan of Fitzgerald’s seminal work, I used to idolise Gatsby as a romantic enigma – his worship of the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock was a delicate thing of innocence, like that first teenage crush, something too absurd to exist in our secular, scientific world, yet all the more compelling for it. There was a time when my feelings toward Trump also bordered on this type of hero worship.

As my understanding of both Gatsby and Trump has matured, I’ve become less idealistic. Both are flawed characters, given to exaggeration, and self-aggrandisement. Both constructed lavish legends around their own personal brand and sought the approval of society to augment their enormous egos. Yet at the heart of each lies a boyish whimsey – a simple and somewhat naïve yearning to return things to the way they used to be. And in this we see the fragile flame of hope.

So if Gatsby’s fixation on creating the perfect life for him and Daisy is a metaphor for the nationalism that drives Trump, then what does Daisy represent in this analogy? Be patient, all will be revealed. What matters for now is the idea of hope, and also the book’s sub-themes: frailty, fickleness, and fleetingness.

A popular and plausible interpretation of the novel is that Gatsby is emblematic of the American Dream. In this sense, the central theme of hope is analogous: Gatsby was driven by his dream of finally possessing the object of his love; while the great promise of America is ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’.

But if a burning aspiration to actualise one’s destiny is the lone criterion for a Gatsby metaphor, then we would all be Gatsby to some extent. So, the comparison must go further.

Apart from the cultural phenomenon of Donald Trump which has embodied the American Dream for four decades, there are several striking parallels with Gatsby and his antagonists, not only in the motivations surrounding Trump’s ascension to the White House and his subsequent ousting, but also in the reaction to him of the two demographic mainstays of the United States: The establishment, and the people.

Let us now explore these.

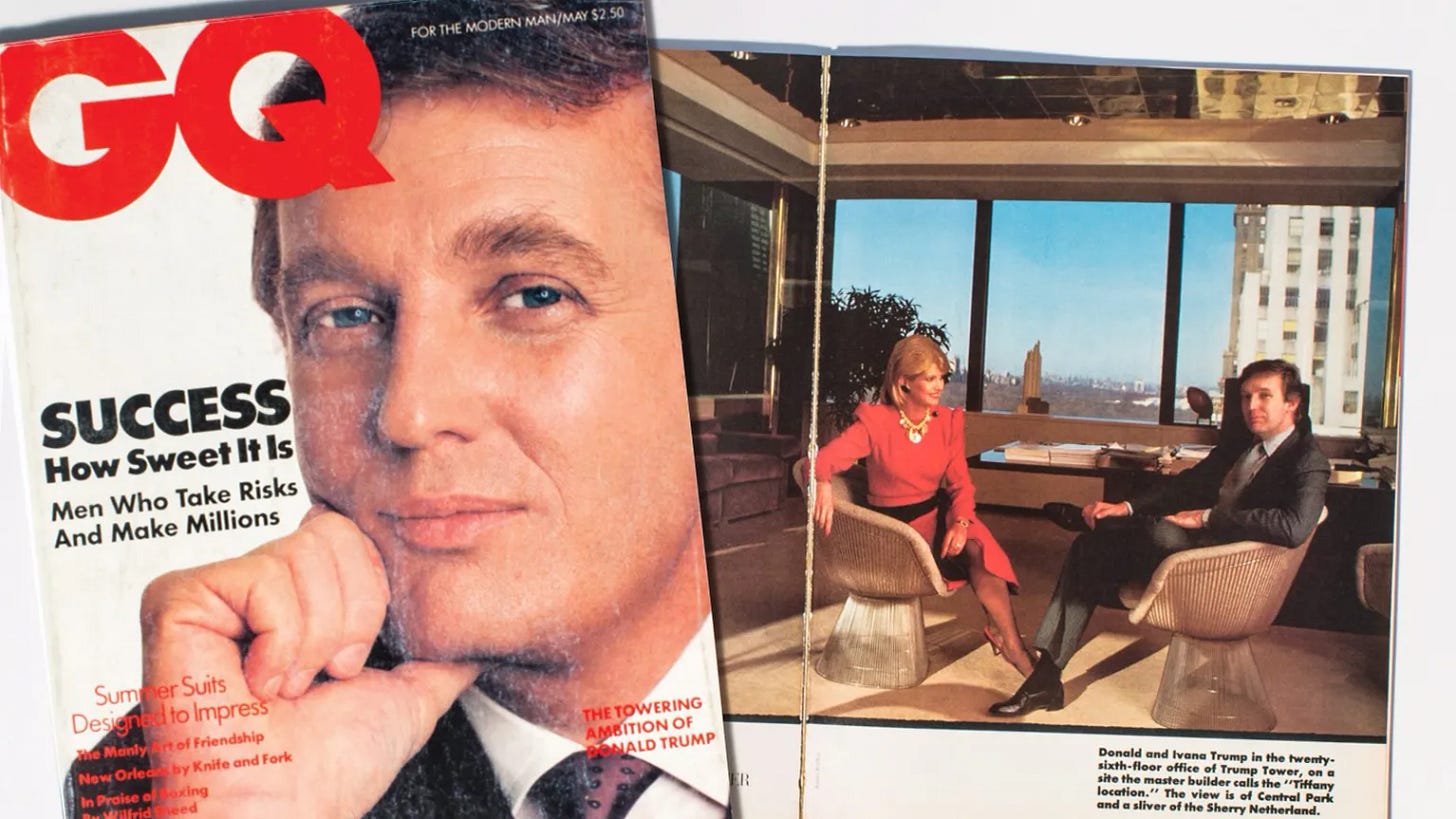

The comparison truly begins with the flamboyant, self-made billionaire embodied in both Gatsby and Trump. In fact, the intersection of these two characters, if taken on their glitzy, King of New York personas alone, may be the quintessential example of life imitating art in modern America. Granted, Gatsby was better spoken and better dressed, and his Oxford airs stand in sharp contrast to Trump’s boorish real estate mogul shtick, but the parallel remains.

Like Gatsby, Trump captured the popular imagination, his name spoken with a breathless reverence as people marvelled at the opulence he embodied. In Trump we see a macro version of the Gatsby legend – the rough-around-the-edges go-getter, appearing as if out of nowhere (and not without scandal and scuttlebutt) to become one of the richest and most talked about celebrity businessmen of his time. The parties, the press, and the paparazzi swirled around Trump just as they flocked to Gatsby.

Here now the metaphors begin coming to life. In the frenetic pilgrimage of New York’s smart set to Gatsby’s Long Island mansion every weekend we see liberal America’s obsession with Donald Trump. This obsession began in the 1980s and burned furiously right up until the fabled moment he came down the golden escalator. At this point something happened – the sentiment abruptly changed.

Donald Trump had overstepped the line, extending his grasp toward something precious that the establishment would fight fiercely to retain. Thus, not surprisingly, Tom Buchannan represents the establishment – the permanent, monied class that sits above the government. The modern aristocracy.

Never an American blueblood, Trump was always the outsider who’d fought for his place at the table and the establishment tolerated and indulged him as it suited them. In the same way, Tom is somewhat ambivalent about Gatsby in the beginning – uninterested, mildly scornful, but happy enough to have him over for lunch, and attend one of his parties.

It is when Tom discovers Gatsby’s intentions toward Daisy that he becomes truly hostile, and immediately a chain of events is set in motion that ultimately leads to Gatsby’s downfall. By dint of his base cunning and his ability to dominate the servile mechanic Wilson, Tom swiftly engineers Gatsby’s demise.

It is not important who Wilson represents in our analogy – pick your functional organ of American national life: the intelligence agencies; the media; the Democratic Party – essentially one and the same. What matters is – Gatsby threatened Tom’s control of Daisy, Tom used his status to manipulate Wilson, and Wilson put an end to Gatsby.

Speaking recently on Timcast IRL Donald Trump Junior recalled how when his father announced his candidacy, he and the rest of the family were immediately ostracised from the trendy neoliberal ‘cool kids’ scene. Former friends vanished, invitations to the big Manhattan parties ceased, media sentiment pivoted from worshipful to vitriolic overnight. The Trumps were abandoned by a previously adulating social class.

We see this mirrored at Gatsby’s funeral which is only attended by his father and servants, and the narrator Nick Carraway. One of the party guests (Owl-eyes) does eventually show up to the burial. “I couldn’t get to the house,” [for the funeral] says Owl-eyes to Nick. “Neither could anybody else,” Nick says [and we can assume a sardonic tone here]. “Why, my God! They used to go there by the hundreds,” Owl-eyes exclaims.

It is remarkable how analogous Gatsby’s funeral is to Trump’s treatment by liberal America once the establishment designated him persona non grata. Here we see the fickle nature of fame and public adoration – in the same way that Gatsby’s wild jazz parties had made him popular with the well-to-do of New York in the Roaring Twenties, so too had Trump’s flamboyance and ultra-boss-man persona propelled him to the top of the Big Apple’s pecking order in the vapid Eighties. But none of it meant anything in the end.

Human frailty breeds a hive mind which coalesces around power structures and shuns heretics of the orthodoxy. Trump, like Gatsby, banked on his popularity and the sparkling allure of his great wealth to serve his cause – and to a certain extent it did. But it also served to hobble him.

As Michael Jackson said, the bigger the star the bigger the target, and Trump spent most of his time in office rebutting attacks on his integrity – the same tactic that was employed against Gatsby in life (by Tom at the Plaza Hotel when he attempts to discredit Gatsby in front of Daisy) and indeed in death as the newspapers spun up the “grotesque, circumstantial” story of his passing.

It did not matter to the hordes of glittering Manhattan socialites what wonderful times Gatsby’s hospitality had afforded them – he had fallen out of favour and thus had to be forgotten. Likewise, liberal America fell obediently into line when the Trump narrative switched.

Who then does Nick Carraway represent? when he calls back up to Gatsby from the garden on that final morning: “They’re a rotten crowd. You’re worth the whole damn bunch put together.”

Why, Nick is us of course.

For those of us who still believe in the Trump story arc and wish to see it happily concluded, Nick Carraway’s famous last words to his friend Gatsby have a poignancy that borders on the sublime as we witness the ongoing persecution of a man who simply wanted to make America great again. A flawed man to be certain; an idealistic man who naïvely thought he could take on the system without repercussions – but an exceptional man; a man who “believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us.”

The Great Gatsby teaches us that people are fickle, happiness is fleeting, and that maybe it is impossible to resurrect the past. But it also shows us the power of hope.

At the closing of the novel, Nick sits on the beach before Gatsby’s deserted mansion:

And as I sat there brooding on the old, unknown world, I thought of Gatsby’s wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. He had come a long way to this blue lawn, and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.

As Donald Trump faces down the establishment for what is perhaps the last time – we must ask ourselves, is the dream behind us? Or can we repeat the past?

After Daisy accidentally runs down and kills Myrtle Wilson and Tom pulls her back into his sphere of control, Nick becomes unenamoured with Daisy, his hitherto beloved cousin – sweet Daisy, once so fresh and innocent, corrupted by the trappings of Tom’s immense wealth and bamboozled by his gaslighting – Nick reflects that “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy – they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

As the machine gears up to crush Trump once and for all we ask ourselves if Donald Trump will get to complete his story arc and write the sequel that poor old Gatsby never got. We ask ourselves, is it even possible, not only to repeat the victory of 2016, but to return the Western world to a place of pragmatism, prosperity, decency? Or has America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, retreated into such vast carelessness as to stake this final roll of the dice instead on the crumbling, cancerous edifice of the Liberal World Order? Is the soul of America still intact?

I know I said I would reveal the meaning of Daisy Buchannan in this American allegory. I was going to end by specifically naming her metaphor – but, my dear readers, you are intelligent people, and the answer has already been given. I shall leave it to you to discern, and from thence to ponder the implication.